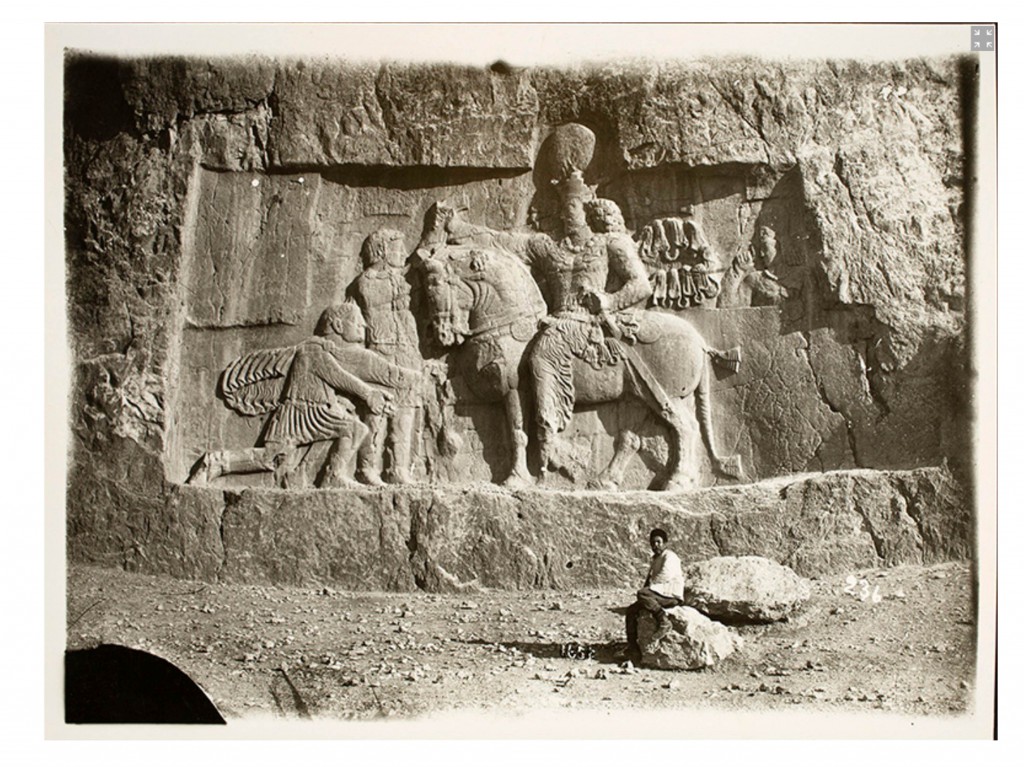

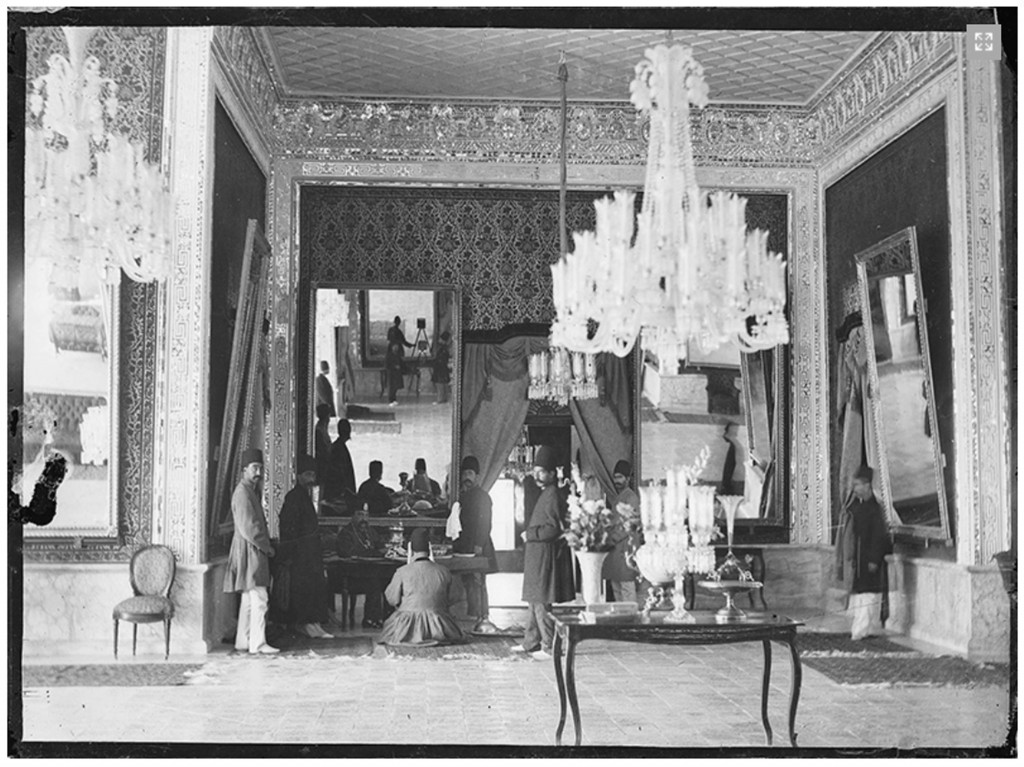

Sevruguin took photographs of landscapes, monuments and people – nomads, workers, women, even the Royal family. Many of Sevruguin’s surviving glass plates are well-preserved at the Smithsonian but his beautifully detailed work remains largely unknown.

During the last few years of his life, Sevruguin’s studio was run by his daughter Mary. She was able to recover some of his glass plate negatives, perhaps through her friendship with Moḥammad Rezā Shah (r. 1941-79). Sevruguin died of a kidney infection in his late nineties and was buried in the family tomb in Tehran.

Of the more than 7,000 glass-plate negatives that Sevruguin made, only 696 have survived. These remaining negatives were eventually bequeathed to the American Presbyterian Mission in Tehran. It is not known when or by whom these negatives were donated, but they were purchased for two hundred dollars by the Islamic Archives established by Myron Bement Smith in 1951-52, and were eventually donated to the Smithsonian Institution where they are now housed in the Freer Gallery of Art and the Arthur M. Sackler Archives (Ballerini, pp. 99-117).

Sevruguin’s father, Vassil de Sevruguin, of Armenian origin, was a scholar of the orient and a Russian diplomat. His mother, known only as Achin Khanoum, was of Georgian extraction. Both were Russian subjects. They had seven children, all born in Tehran. Although the father was an employee of the Russian government, the family was denied a state pension when he died after a riding accident. Achin Khanoum and the children returned to her native Tbilisi, and shortly afterwards to Akoulis, a smaller and more affordable town. Antoin and his brothers Kolia and Emanuel attended school there, while the eldest brother, Ivan, entered the military academy as a cadet. Later, Ivan was exiled to Siberia for his political activities. This, and the denial of the pension, made the family feel resentful towards Russia.

Antoin decided to return to Tbilisi and continue his studies in painting and photography. There, he befriended the Russian photographer Dmitri Ivanovich Jermakov (1845-1916). From 1870 Jermakov traveled regularly throughout Persia, producing 127 albums and 24,556 negatives by the time of his last trip in 1915. Sevruguin decided to emulate Jermakov and carry out his own photographic survey of the people, landscape, and architecture of Persia. He persuaded his brothers Kolia and Emanuel, both businessmen in Baku, to accompany him. Around 1870, they traveled with a large caravan to Persia and took pictures in Azerbaijan, Kurdistan, and Luristan. Finally, they went to Tehran where Sevruguin met and married Louise Gourgenian who came from an old Iranian-Armenian family. They had seven children together (Olga I, Olga II, Mary, Alexander, André, Ivan, and Mikhail).